Grinches, grouches, witches, ogres and brats.

Green is the color of their skin: they are outcasts, different, uncivilized according to authority, they are rule-breakers, unwilling to conform, a danger and disruption to society’s tranquil (or-so) life. They are alien.

With Charli XCX’s brat and Wicked’s Elphaba, green made its mark this year. A vibrant, electric grassy green. We welcomed it. We desired it. Likely, we needed it.

Now, as a believer in the masterpiece that is Shrek, I recognize that green-skinned characters have captured hearts within literature and pop culture over the last century, some with terror and some with obsession. But, why green? Why this specific shade of green? Is it a symbol, a message, or has it simply been a nice color to choose?

I wanted to trace back the first documented mentions of “green people”, so I did some research.

The green children of Woolpit and the green sickness

Sometime during the 12th century, the legend of the green children of Woolpit emerges. The legend speaks of a brother and a sister with green skin who reportedly appeared in the village of Woolpit in Suffolk, England around 1100s, presumably during the reign of King Stephen. They spoke in an unknown language and ate only raw broad beans. Eventually, they learned to eat other food and lost their green color, but the boy became sick and died. The sister was left to navigate this new life alone, considered to be "very wanton and impudent" by the village. You can find this legend mentioned in William of Newburgh's Historia rerum Anglicarum and Ralph of Coggeshall's Chronicum Anglicanum, written in about 1189 and 1220. Later, the green children are mentioned in William Camden's Britannia in 1586, and in two works from the early 17th century, Robert Burton's The Anatomy of Melancholy and Bishop Francis Godwin's The Man in the Moone.

Explanations for the green children vary and continue to be sought, but these dominate: A story descending from folklore, describing an imaginary encounter with inhabitants of a “fairy Otherworld” believed to be extraterrestrials. Or, a story rooted in real events, depicting indigenous Britons or Flemish immigrants.

Historian Derek Brewer also has an explanation:

The likely core of the matter is that these very small children, herding or following flocks, strayed from their forest village, spoke little, and (in modern terms) did not know their own home address. They were probably suffering from chlorosis, a deficiency disease which gives the skin a greenish tint, hence the term "green sickness". With a better diet it disappears.

I hadn’t heard of the green sickness before.

First described in the 16th century, chlorosis was believed by many physicians to be a nervous disorder, and was classified as a hysteria disease. It primarily affected teen girls and young women, as it affected the menstrual cycle during puberty. By the end of the 19th century, the disease increased. But its true nature was still unknown. Physician Thomas Sydenham advised treating chlorosis with iron supplements but his recommendation was ignored. Now considered iron-deficiency anemia, reports of chlorosis stopped being reported after the 1930s, presumably due to better diagnostics and changes in the social position of women.

Could our great fictional green-skinned characters be inspired by chlorosis? Perhaps not directly, but the green children of Woolpit may have.

Centuries later, the legend inspires English anarchist poet and art critic Herbert Read’s only completed novel “The Green Child”.

The Green Child and the Wicked Witch of the West

Published in 1935, The Green Child follows Olivero, dictator of the South American Republic of Roncador, who staged his own assassination, and returns to his hometown, an English village, where he meets Sally, a green-skinned girl he recognizes to be one of the two children who had mysteriously arrived in the village on the day he left, 30 years earlier.

This cover’s green might be my favorite green.

1935 is a few years before we see our first vibrant, electric green-skinned human on a television screen.

In 1939, The Wizard of Oz premiered, featuring a witch with green skin.

In the books, L. Frank Baum describes her to have one eye, a magical diamond and red ruby-covered golden cap, a variety of animal slaves, and a beautiful castle decorated in yellow velvet rugs, yellow silken draperies, and yellow antique decor. (Ah, a woman of taste.) She is illustrated as an old hag with pigtails.

But, is not green.

So, what inspired The Wizard of Oz’s filmmakers to choose green skin for the film? Is the vibrant technicolor film the only explanation, or could a book published a few years prior have sparked an idea?

I believe we stand on the shoulders of who came before us. Behind every art piece, is an art that inspired it, even if just subconsciously. Artistic choice is rooted in the past.

To me, The Green Child and the Wicked Witch of the West’s green skin exist on the same wavelength. The great 12th century mystery of the tale of the green children had made its way to 1939, 800 years later.

The meaning of green

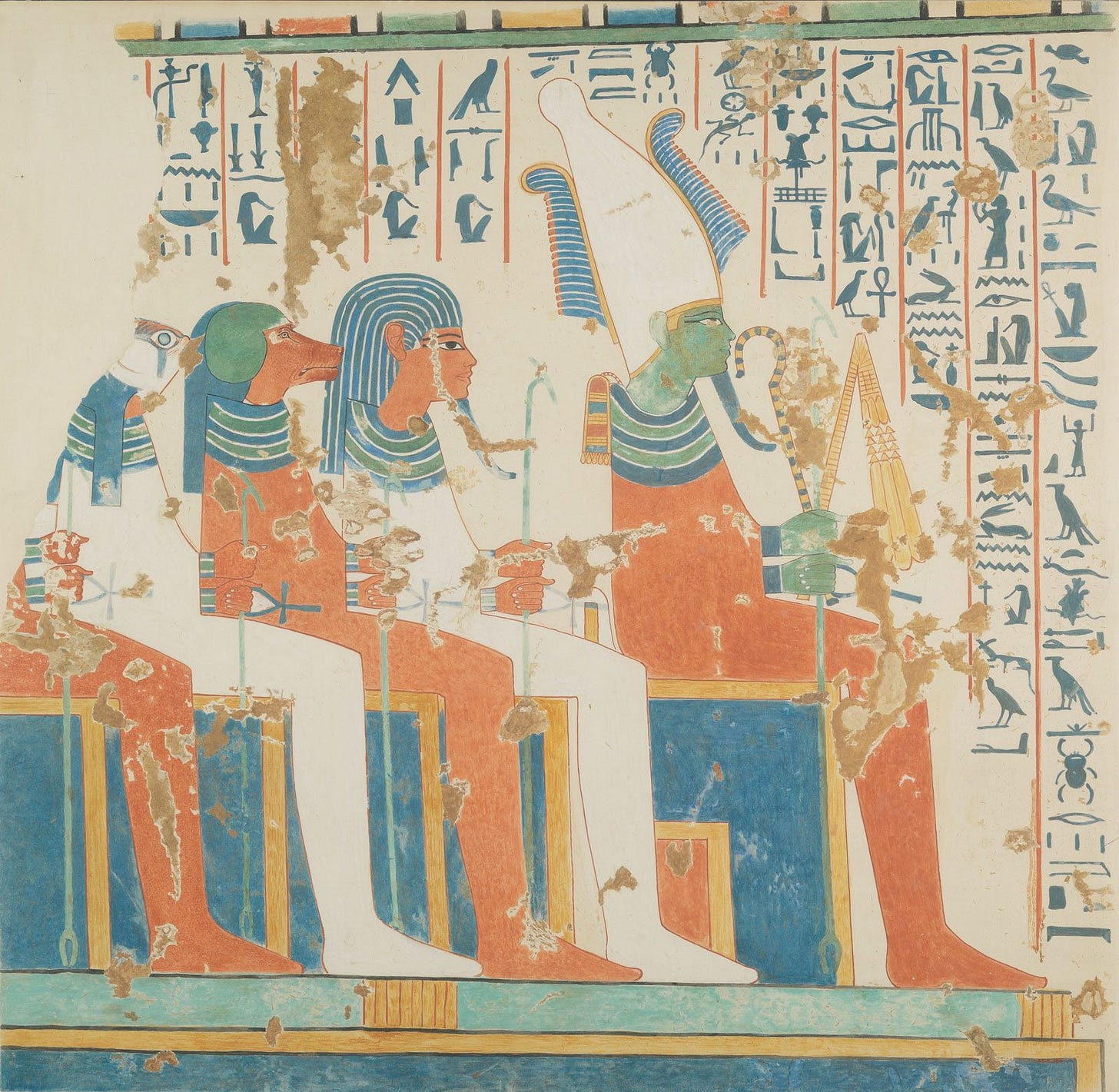

Green is the color of grass, of leaves and tress, of spring. It is nature, it is growth. It is also associated to health, birth, rebirth, fertility, and women. Osiris, the Egyptian god of fertility, agriculture, the afterlife, the dead, resurrection, life, and vegetation is depicted with green skin.

Green then also becomes associated with otherness [“fairy Otherworld”] and sickness. And might I add, more specifically, with roots to puberty, menstrual cycles, and teenage girls. It doesn’t feel entirely out of the blue, then, that the first green-skinned character portrayed on screen is a woman.

Following The Wizard of Oz, Mayaya's Little Green Men by Harold Lawlor is published in Weird Tales, an American fantasy and horror fiction pulp magazine, in 1946. We then see an increase of green alien tales in the 1950s. Green is now martian, it is invasive, and comes with its own agenda.

As more green-skinned characters emerge within pop culture, like Stan Lee’s The Hulk (1962), Dr. Seuss’ The Grinch (1966), Sesame Street’s Oscar the Grouch (1970), or William Steig’s Shrek (1990), we see a common thread. Characters who stand out, who don’t fit societal norms, who live isolated or alone, looking down upon the civilized; the “Other”. Like the Wicked Witch of the West, their green skin disrupts and threatens. And as we know, this isn’t fictional. Society marginalizes, categorizing race, economic status, sexuality, immigration status, mental state. When threatened, it looks for someone to blame.

A longing for commotion

In Carrie Bradshaw’s words, I can’t help but wonder if our green takeover this year goes a little deeper than just a love for aesthetics?

"I don't cause commotions, I am one."

Elphaba, written by Stephen Schwartz, “Wicked” (The Musical)

Our collective embrace of the Wicked, bratty green (#9bca47) may in fact reveal an underlying longing for societal disruption, a shakeup of the status quo, a change. We connect and empathize with green’s Otherness. We long to be like it, envious of its power. Perhaps, even, we see ourselves in the green. After all, nothing in life is simply black and white.

A color used to isolate is 2024’s subtle cry for unity.

When I put these green characters side by side, I’m overwhelmed by their humanness. Confidence even in the face of rejection, frustration and anger, political protest, loneliness, pain…they represent the deepest parts of being human. A protest, a cry to return to nature’s roots.

A loud green dominating this year was surely not coincidental.

In “To Hell with Culture: And Other Essays on Art and Society”, Herbert Read writes:

Art is always the index of social vitality, the moving finger that records the destiny of a civilization. A wise statesman should keep an anxious eye on this graph, for it is more significant than a decline in exports or a fall in the value of a nation's currency.

In The Green Child, the green-skinned girl is first introduced tied up. Once liberated, she continuously resists being tied down. She refuses to behave like a conventional heroine, and essentially, leads Olivero to his enlightenment. There is always truth in fantasy.

I conclude with this: in painting, a technique is used to bring out flesh tones and make human skin appear more authentic. Painters will use green as a background, and paint the flesh tones over it. Because green is a complimentary color to red, this underpainting technique helps skin tones “pop out”.

I’m not sure how this next year will unfold, what heaviness or pain we’ll feel, or what we’ll go through as a collective, but what I do know, is “art is always the index of social vitality”. And like an underpainting, the color green may just be what we need as a society to reveal what has otherwise been hidden.